Why haven't we blacked out the Internet again?

On January 18, 2012, millions of Americans woke up to an error message. It wasn't a glitch.

On January 18, 2012, millions of Americans woke up to an error message. Wikipedia went dark. Reddit was down. I was working at Grooveshark, one of the biggest music streaming sites in the world. Our site, along with more than 100,000 others, was showing the same message.

It wasn't a glitch. It wasn't hackers crashing servers from the shadows. It was something far more powerful. A protest. The internet had gone to war. And it was going to win.

The bills we were fighting, SOPA (in the House) and PIPA (in the Senate), were designed to give the government control of the free and open internet, a veto on every website, a switch to turn them off without so much as a public hearing, let alone due process. Their introduction followed a string of escalating parries back and forth between legacy media and the fledgling tech companies. One gasping to maintain its status. The other, desperate to enable the next generation of creators.

Legacy media had spent their war chests on lobbyists and hill visits, deployed their unlimited budgets trying to cut down the sprouting tech companies with headline-grabbing lawsuits meant less to win than to terrorize. Scare off partners. Intimidate advertisers. Generate threats from state Attorneys General.

Grooveshark was the first global music streaming site, operating in 24 languages in every single country in the world. We were the YouTube of music. No gatekeepers. No barriers to entry. No intermediaries. Just creators with direct access to their fans. We were disruptive, and we had the battle scars to prove it.

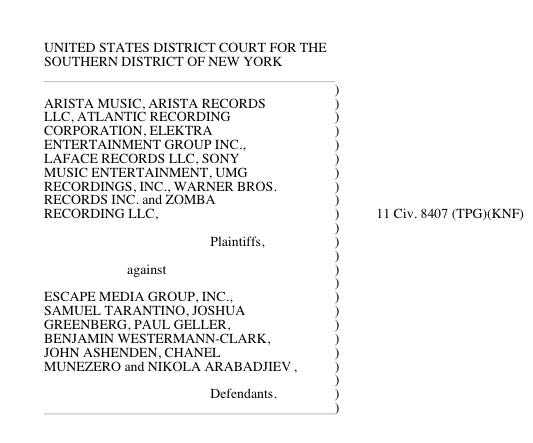

We were on the receiving end of more than one lawsuit during my tenure as the head of the data team and then the head of their government affairs department. I was personally named in the notorious $17 billion case: Arista et al v. Escape Media Group,

or as it read when I was served: UMG Recording, Inc., Atlantic Recording Corporation, Zomba Recording L.L.C., Elektra Entertainment Group Inc., Arista Records LLC, LaFace Records, LLC, Warner Bros. Records Inc., Arista Music and Sony Music Entertainment v. Escape Media Group, Inc., Samuel Tarantino, Joshua Greenberg, Paul Geller, Benjamin Westermann-Clark, John Ashenden, Chanel Munezero and Nikola Arabadjiev.

But these bills were to be their coup de grâce against the open internet. The studios marshaled the full weight of Hollywood, major record labels, and nearly every major content company in America. Sony, Universal, Disney. A constellation of incumbent power that had never known defeat. But they had overreached, and this time, the internet would fight back.

The mechanics of the blackout weren't complicated. Fight for the Future, a digital rights organization, coordinated the effort through private listservs and direct outreach. They didn't just recruit tech giants; they organized thousands of smaller sites, personal blogs, independent forums. The power would come from volume, not prestige.

Reddit committed first to a 12-hour blackout. The announcement sent ripples through the tech community. Wikipedia's community voted overwhelmingly to join for 24 hours. At Grooveshark, we didn't hesitate. We were already in the crosshairs of these very same forces trying to push SOPA through Congress. The cascade was swift. Once the major platforms committed, smaller operators felt permission to follow.

There was no central command that could be co-opted. No single leader who could be bought off. Just thousands of independent decisions to act in coordination. We each added a simple piece of code that would activate on the same day at the same time, replacing our content with information about the bills and direct links to congressional contact forms. It was elegant in its simplicity and devastating in its effectiveness.

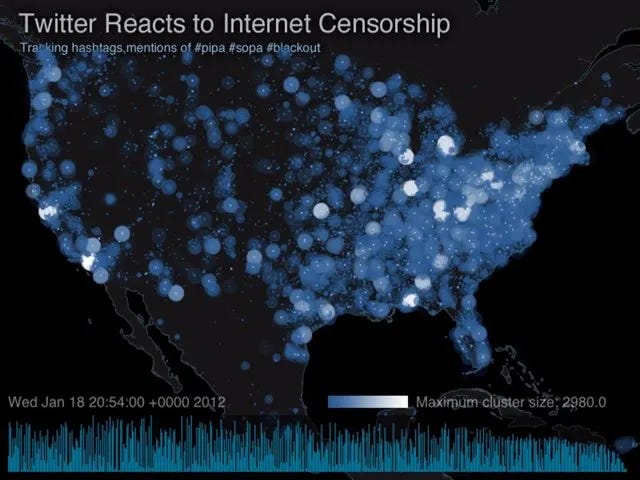

When every screen you loaded showed the same message, the message became impossible to ignore. Within 24 hours, 162 million people had seen Wikipedia's blackout message. Google collected 4.5 million petition signatures. For the first time in history, congressional email servers had buckled, broken, and become overloaded under more than a million messages.

Forty-eight hours later, 18 senators had withdrawn their support. By January 20th, both bills were effectively dead. It was the most successful act of coordinated digital resistance in history. A perfect demonstration of what the internet could accomplish when it moved as one organism instead of billions of separate voices shouting into the void.

So here's what I can't wrap my head around: Why haven't we done it again?

We had proven that coordinated digital action could kill legislation backed by some of the most powerful lobbying forces in Washington. We demonstrated that congressional servers could be overwhelmed, that public opinion could be shifted overnight, that the internet could defend itself when it chose to act collectively.

But we've never built on that victory.

Since 2012, we've become masters of organizing in physical space, even using digital tools to do so. We know how to fill plazas and pack stadiums. We've perfected phone banking and door knocking. We can coordinate millions of people for marches and rallies with unprecedented sophistication and coordinated messaging across time zones and territories. But it almost never seems to move the needle. Sure, we can get press and own the conversation for a few hours online, but it's not changing legislation. It's not moving our lawmakers anymore.

Here's why. They live online now. They get their information from digital feeds. Their understanding of public sentiment is filtered through social media metrics, algorithmic recommendations, and engagement data: upvotes, ratios. Protest is easy to ignore if it never reaches the volume or influence of the average presidential bleet.

We are fighting for the attention of people who experience reality primarily through screens, and we've abandoned the one tactic we proved could capture their attention completely.

It's not for a lack of infrastructure. The infrastructure is still there. WordPress powers 40% of all websites across the world. Substack hosts thousands of independent newsletters. Personal blogs and forums continue to thrive.

The technical capacity for coordination is greater now than it was in 2012, not less. But we act as if we're powerless, as if the internet is something that happens to us rather than something we create.

We tweet our outrage into algorithms designed to optimize engagement, not political impact. We sign petitions that disappear into databases. We share articles that get buried beneath sponsored content and AI-generated slop.

Meanwhile, buried in our collective memory is proof that we once made the most powerful lobbying operation in Washington back down in mere hours.

In 2012, we were fighting against censorship. In 2025, things feel eerily similar, and the incumbents are not all that different. Perhaps they're more integrated with the government. Perhaps the government is less responsive. Perhaps the open Internet no longer feels like the underdog. But perhaps the threat to speech is more dire than ever.

The question isn't whether we have the technical capacity to coordinate something as impactful as we did in 2012. We surely do. The question is whether we remember that we have this power. That every website that goes dark represents thousands and thousands of votes. That every coordinated silence is a form of speech. That when government becomes unresponsive, you have another choice. You can comment on their feed. Or you can turn it off until they listen.